On December 10 Representative Rashida Tlaib, Congresswoman from the Michigan 10th District tweeted: “I’d like to wish my Jewish neighbors a Happy Hanukkah. Hanukkah inspires me, especially during this difficult time. I hope we can all remember that even in the most unexpected moments, miracles can happen.” The Tweet seems innocuous, no different than probably hundreds of such messages which politicians send to their constituents, or to the broader public, wishing all a happy holiday. Representative Tlaib also included some sweet pablum about miracles, saying she herself draws inspiration from the holiday in this difficult time.

Justin Amash, the Libertarian Congressman from Michigan’s 3rd District tweeted: “Wishing a blessed and happy Hanukkah to all who celebrate!” Representative Dan Kildee of Michigan’s Fifth District tweeted: “Happy #Hanukkah to everyone in mid-Michigan and around the country celebrating the first night of the Festival of Lights! Even though this holiday looks different this year, I hope happiness, love and hope fill your homes for the next eight day and many more to come.” Congressman Kildee added a Hanukkah emoji and a photograph which showed a menorah with eight candles and a present. While Flint has a few synagogues and a long Jewish presence, there are not that many Jews in the area represented by Kildee. His greeting, like those of the other politicians were not so much de riguer as the signs of civility. Before a religious holiday it is befitting for a political leader to wish those who celebrate that holiday a happy holiday. If they want to go the extra step, like Kildee, and show some understanding of the holiday (“first night” “eight days”)—great. If they want to draw some inspiration from the meaning of the holiday, even better. However, even the boilerplate greeting that Justin Amash sent is a welcome sign of civility in our civic culture.

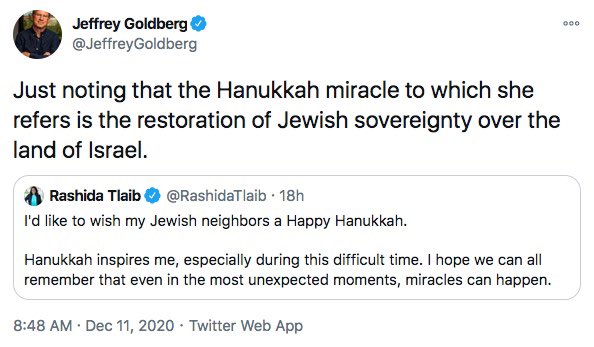

It was somewhat striking then that Jeffrey Goldberg, the editor of the Atlantic, who happens to be Jewish, decided to “dunk” on Tlaib. First thing the next morning, Goldberg retweeted Tlaib’s tweet with the comment: “Just noting that the Hanukkah miracle to which she refers is the restoration of Jewish sovereignty over the land of Israel.” The “just noting” introduction is the Twitter giveaway that the following comment is significant and cutting. It seems that Goldberg thought that Tlaib was aligning herself with Ancient Jews whom she would not align herself with had they lived today. In other words, Goldberg seems to be implying that Tlaib is mistakenly or hypocritically celebrating Jewish restoration of sovereignty over the land of Israel, while at the same time she is a supporter of Palestinian rights.

So, first, Goldberg’s comment replaces the discourse of civility—politician wishes their constituents well—with the more common Twitter idiom of political snark and sarcasm. The Tweet also, perhaps inadvertently, placed itself in the middle of the Hanukkah controversy itself. Many Jewish Twitterati immediately replied to Goldberg that he was getting the holiday wrong, and that the miracle of Hanukkah was actually the cruz of oil which burned for eight days. Goldberg is a learned Jew and therefore he would have known this. In fact he probably knows that there are two different miracle stories which are in tension and perhaps in conflict with each other.

There are two prayers that are unique to Hanukkah. One is said in Jewish rites, in the amidah prayer which is recited thrice daily. The second is a liturgical poem, recited in Jewish communities of European origin during the candle lighting ritual. In the first prayer, also known as al hanisim/about the miracles, the miracle that is extolled is the victory of the few over the many, the righteous over the wicked. In the liturgical poem (maoz tzur translated unfortunately as “Rock of Ages”) the miracle is that when there were not enough cruses of sanctified oil, the sanctified oil that was left lasted for eight days.

Goldberg’s choice of the military victory is not a neutral choice. The rabbis of the Talmud, the 6th century Babylonian Jewish text which expounds on Hannukah in all its legal complexity for the first time, chose the miracle of the oil and glossed over the military victory. The rabbis were not very fond of the Hasmonean house which descended from the Maccabees, so this may not be surprising. They also preserved an acute memory of the death and destruction which accompanied the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE and the Bar Kochba revolt in 135 CE. The rabbis of the Talmud have a strong preference for pacifism.

However, pacifism did not serve the nascent Zionist movement well, and so when searching for militant ancestors they could find none better than the Maccabean band of zealots. The Zionist movement resurrected the fight for national sovereignty from the dust of the extracanonical books of the Maccabees.

This Twitter scrap played out as it did because of the two registers in which everything religious plays out in today’s political realm. Christian, Muslim, Jewish, have all become fighting words. Any Tweet that a Muslim-American politician tweeted on a Jewish topic would be scrutinized for its political content. It would not and did not matter that the message was a human message not on the field of battle. Goldberg is picking up a cudgel from another fight that is obviously not yet over for him.

The call for civility is usually a call for the weak to disarm and not to use the weapons of the strong. However, there is great benefit when around the margins there is a recognition that the battleground has boundaries. There is no glory when the Jewish editor in chief of one of the magazines which sets the intellectual agenda for the public space dunks on a Muslimah Congresswoman of color on an issue which was obviously not on the field of battle.

_______________

Dr. Annette Yoshiko Reed has a phenomenal Twitter thread with links if you want to really geek out on the history of Hanukkah.

Tonight we light the fourth Hanukah light.

Tonight we light the fourth Hanukah light.